No early Church Father (typically defined as writers from the 1st to 5th centuries, especially ante-Nicene and Nicene eras) explicitly denied or rejected the intercession of departed saints in a clear, systematic way — that is, no major patristic figure wrote a treatise or statement outright condemning the belief that saints in heaven can pray for those on earth or that the living might benefit from their prayers to God.

The practice of invoking (directly addressing or praying to) departed saints for their intercession developed gradually. Historians note that explicit evidence for seeking the saints’ help and prayers accumulates especially from the 3rd century onward, building on the earlier veneration of martyrs (honoring their relics, tombs, and anniversaries).

Key Points on the Historical Development

- 1st–2nd centuries: Focus was on honoring martyrs (e.g., Martyrdom of Polycarp, mid-2nd century) through memorials and relic preservation. No clear evidence of direct invocation of the dead, but the groundwork for the communion of saints exists (e.g., belief that martyrs are with Christ).

- Early 3rd century: Some fathers appear to assume or imply that saints (including departed ones) intercede, while others do not mention or seem to limit prayer strictly to God. Scholars like J.N.D. Kelly observe that “evidence for the belief in their intercessory power accumulates” in this period.

- Later 3rd–4th centuries onward: Clear affirmations appear (e.g., Origen on angels and saints praying, Cyprian on mutual mindfulness after death, and later fathers like Basil, Gregory Nazianzen, and Augustine).

Fathers Sometimes Cited as Opposed or Limiting

Certain ante-Nicene figures are occasionally interpreted by Protestant apologists as not supporting or even implicitly against invocation, because they emphasize prayer to God alone or lack positive references to asking departed saints. However, these are absences of evidence rather than explicit denials:

- Tertullian (d. c. 220) and Clement of Alexandria (d. c. 215): Sometimes described as appearing to “reject” the idea due to silence or emphasis on direct prayer to God. No explicit condemnation exists in their surviving works.

- Cyprian of Carthage (d. 258): Some claim his writings limit intercession, but others note he encourages mutual prayer and implies it continues after death.

- Origen (d. c. 254): Affirms that angels and “souls of the saints who have already fallen asleep” pray for the living (in On Prayer 11), though he does not explicitly instruct direct invocation.

- Vigilantius (late 4th century): A presbyter who did criticize prayers to saints, veneration of relics, and related practices. However, he was not a Church Father — he was opposed by St. Jerome, who defended the practices in Against Vigilantius.

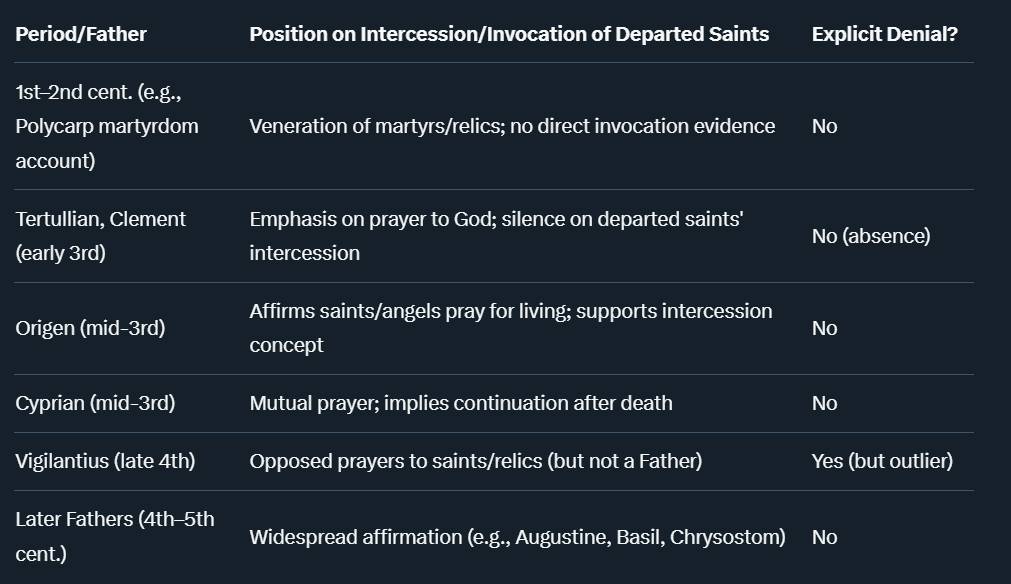

Summary Table of Early Views

In short, while the full practice of invoking saints (as later formalized) was a development and not universally attested in the earliest centuries, no orthodox early Church Father explicitly denied the core idea of the intercession of departed saints. The earliest opposition came from fringe figures like Vigilantius, who were refuted by the mainstream tradition. This aligns with the gradual emergence of the doctrine, rooted in the communion of saints.

Leave a Reply